By Craig Walker

Creating A New Transit System From Scratch

In the late 1950s, even as the Key System streetcar and suburban train system was being dismantled (the final Key System train over lower deck of the San Francisco to Oakland Bay Bridge occurred in 1958), traffic in the San Francisco Bay Area was well on its way to becoming untenable. The area’s population was growing, and due to the geography of the Bay Area the bridges connection various parts of the metropolis were becoming the source of routine delays. This affected commutes and shipping, as well as pleasure trips. The San Francisco Peninsula had a solid system in place thanks to the Southern Pacific Railroad’s “Commutes” connecting “The City” (as the locals refer to San Francisco) and San Jose, forty-five miles to the south.

A transit study in the 1950s concluded that a high-speed rapid transit system, which would link the area’s cities with newer suburban areas, would be the most cost-effective solution. The Bay Area Rapid Transit District was set up in 1957 to study such as system, with representatives from the Bay Area’s five counties (Alameda, Contra Costa, San Francisco, San Mateo and Marin). And as can be expected with planning a complex system such as this, along the way there were minor, and sometimes major, setbacks.

Initially, one county opted to not join this District, as Santa Clara County supervisors felt that, thanks to preliminary studies, what would become BART would not serve their county well. The supervisors opted instead to concentrate on expanding the South Bay’s freeway system. (Plus, they were already connected to San Francisco by rail thanks to SP’s Commutes.) By 1962 San Mateo County, also on the peninsula, opted out as well and without their tax revenues, Marin County, across the Golden State Bridge from San Francisco, also left the District. These changes to the District’s members resulted in a transit system that would be smaller than originally envisioned. However, this also kept the District’s focus on a smaller system that could be constructed more quickly and, theoretically, for less money.

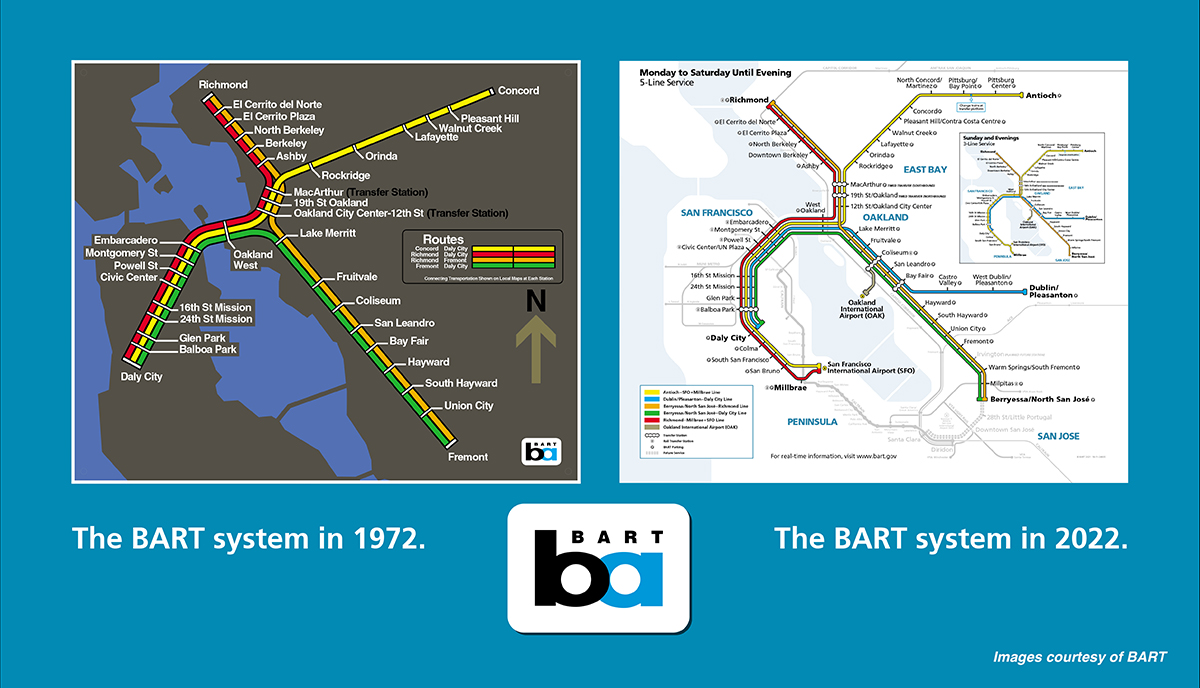

By 1962 this new transit system was submitted for approval to the remaining counties’ voters and, liking what they saw, voted to approve moving forward. This initial plan would form an X-shaped system with terminals in Concord to the northeast, Daly City in the southwest, Fremont to the southeast and Richmond in the northwest. Tracks connecting San Francisco to Oakland, the area’s two largest cites, would pass under the San Francisco Bay’s waters.

An entirely new transit system was a radical idea in the late 50s and early 60s, a time when most cities were paring their existing transit systems back, if not outright removing them (as the Los Angeles area did with the Pacific Electric Red Cars, the final line of which was removed just one year before BART was approved by voters).

In 1964 construction had begun on the new Bay Area Transit System, which included several major engineering challengers: Subway tunnels needed to be excavated in downtown San Francisco, Oakland and Berkeley; elevated trackage was to be constructed through much of the rest of the Bay Area (in particular in densely-populated Alameda County and hilly Contra Costa County); boring tunnels through the Berkeley Hills to access Contra Costa County to the east; and most impressively dredging a trench across the floor of the San Francisco Bay into which precast-concrete tube sections would be set to create BART’s iconic Transbay Tube.

BART’s goal was to connect heavily-populated urban centers with newer suburbs, often paralleling established freeways. The trains’ higher speeds and frequent service (six minutes between trains on most lines throughout most of the day).

Opening Day … And Expansions

One September 11, 1972, BART’s first line, between MacArthur (in Oakland) and Fremont, opened for use. Other segments opened as they were completed, with the final major section through the Transbay Tube (connecting the system’s two largest cities) opening in 1974.

Before the system had opened, planners were already designing future extensions. It took over 20 years, but extensions were opened to Colma and Pittsburg/Bay Point in 1996. The original four lines were joined by a fifth in 1997 when a new line was added connecting Daly City on the Peninsula with Dublin/Pleasanton to the east. 2003 saw the opening of an extension to San Francisco International Airport, and in 2014 an automated guideway transit spur was placed in service to connect with Oakland International Airport. Two extensions moved BART into the Silicon Valley, with the Fremont Line extended to Warm Springs/South Fremont in early 2017, and a further extension to Berryessa/North San José in mid-2020. A number of additional extensions are in the planning stages as well.

Silver Trains Snaking Around Northern California

BART’s initial rolling stock was built by Rohr Industries, consisting of 59 A-cars (with cabs) and 380 B-cars (without cabs), with trains consisting of a varying number of B-cars with an A-car on each end. These were supplemented with C1 cab cars from Alstom in the late 1980s.

The Rohr A-cars have a streamlined cab on them, and are numbered 1164-1276. The cabless Rohr B-cars are numbered 1501-1913. The Alstom C1 cars feature a flatter cab, with a door, allowing use – if necessary – as a mid-train car. The C1s are numbered 301-450. Morrison-Knudsen build more C cars (C2) in 1994-1996, virtually identical externally to the Rohr C1 cars. The C2s, no longer in service, were numbered 2501-2580.

These trains operate from electrified third rails, and were built to operate one wide-gauge track. BART trackage was constructed with a 5-foot 6-inch gauge (rather than the standard 4-feet 8½-inches found on freight railroads), providing a smoother ride for commuters and a wider aisle in the cars.

Foresight Rewarded

Fifty years after service began, BART is a Bay Area staple. Its success has no doubt helped spur much of today’s rail transit renaissance in so many North American cities, and not a moment too soon, either, as civilization makes moves away from fossil fuel-powered modes of transportation. Development along BART’s lines has boomed, allowing many to live and work near transit lines.